Give Toronto’s Mayor the Mandate, Team, and Tools to Deliver

Summary

Toronto’s current system makes it hard to deliver on city-wide priorities. Councillors are elected ward by ward, with no parties to connect them to a bigger vision. This feeds localism, entrenched incumbency, and low voter turnout. The mayor has no formal cabinet and no clear executive team, so accountability for results is blurred. Senior staff report to all of council, not through defined leadership, leaving no one directly responsible when projects and systems fail. And the city’s fiscal tools are too narrow to fund growth at scale. The effect is like asking a CEO to run a $20-billion enterprise without a board mandate, without a C-Suite, and without a capital structure — the results are predictable: stalled projects, rising costs, and voters who tune out.

This memo proposes three reforms: (1) introduce municipal political parties to give voters clear platforms and tie elections to council’s performance, providing mayors a city-wide mandate; (2) create a statutory Mayor’s Cabinet of councillors with real portfolios and authority over senior bureaucrats, giving the mayor an executive team to drive results; and (3) expand Toronto’s fiscal powers, paired with fewer, more predictable transfers, so the city has the capital structure to finance growth and act on its priorities.

Target: Pass and enact these reforms at least six months before the October 2026 municipal election, so the next mayor and council can begin their term with the tools to deliver on city‑wide priorities.

Background & Motivation

Imagine a $20-billion enterprise with three million shareholders and daily responsibility for housing, transit, water, and public safety. Now imagine its “chief executive” had no board to set direction, no executive team to drive delivery, and no capital structure to finance growth. That is Toronto. The mayor is elected city-wide but denied the tools any modern leader needs to be accountable: a board-like mandate from parties, an executive team in the form of a statutory cabinet, and a capital structure built on diverse, reliable revenues. Of course, a city is not a business — the responsibilities are broader, the incentives different, and democratic accountability is the goal. But the analogy makes the gap clear: Toronto’s mayor is asked to lead without the basic instruments of leadership.

The system does have strengths: councillors know their neighbourhoods well, and residents often get help on local issues. But at the city-wide level, it collapses. Since 2000, only 12 councillors have ever been defeated in an election; 42 left by retirement or death. Incumbents are rarely unseated because years in office bring name recognition that challengers can’t match. At the provincial and federal levels, voters can sweep out governing parties in “defeat years” when performance fails — 2015 federally1 or 2018 provincially2 for example. Toronto never has those resets. Council is insulated, no matter how well or poorly the city is doing.

Low voter turnout underscores this broken link between elections and outcomes. Turnout collapsed to 29% in 20223 — the lowest in half a century. Federally and provincially, turnout has rarely dropped below twice that rate.

It isn’t apathy; it’s lack of clarity. Other levels of government offer parties with competing platforms that voters can weigh. In Toronto, voters face long lists of independents whose city-wide positions are hard to compare. Residents don’t see how a ward-level vote will affect the city as a whole, so many stay home.

Money is another part of the problem. Global cities like New York and London raise revenue from many sources — property, sales, and income taxes, congestion charges, and borrowing against future growth. Toronto’s toolbox is much narrower. Property taxes, fees, and transfers from senior governments make up most of the budget, and debt is tightly capped. Nearly $3 billion in development charges sit unused4 because projects must be fully funded up front. Without modern revenue tools, Toronto must wait for senior governments to step in. The Waterfront East LRT5 is a prime example: more than a decade after planning began, the project is still unfunded, and residents may move into the Port Lands before transit arrives.

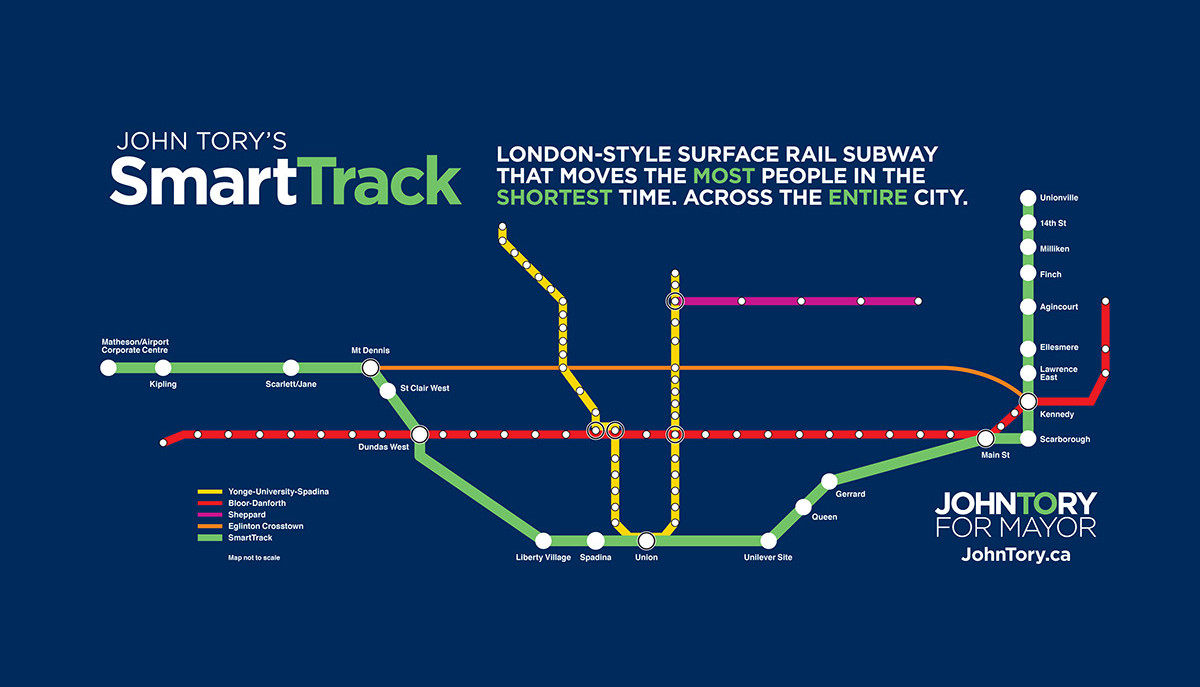

All of these weaknesses are demonstrated in the story of SmartTrack6. In 2014, former mayor John Tory campaigned and won on a signature transit plan to leverage GO rail corridors for a new rapid line. Almost ten years later, there is nothing to show for it. No councillor was elected on this promise, only Tory was. With no mayoral cabinet and no parties to bind council to a shared platform, councillors had no stake in delivery. With no authority over institutions and no fiscal tools, the mayor couldn’t move it forward. For voters, SmartTrack is proof that even when a mayor wins on a clear city-wide promise, Toronto’s system isn’t set up to deliver.

This is the problem that must be solved. Toronto needs municipal parties so voters can connect their ballot to city-wide agendas and hold council accountable for outcomes. It needs a statutory mayor’s cabinet so responsibility for results is clear. And it needs modern fiscal powers — a share of the HST, road pricing, tax-increment financing — so the city can fund and deliver its own priorities. With these reforms, elections would once again be tied to results. Voters could judge platforms, hold leaders to account, and expect promises to be met. Toronto would be able to act like the global city it already is, with the governance tools to match.

Real‑World Solutions

Montreal and Vancouver — Parties create a board mandate. Both cities7 have municipal parties that appear on the ballot, publish platforms, and organize council around a shared agenda. This gives voters clear choices, ties councillors to city-wide outcomes, and makes elections more competitive and accountable.

London (UK) — A cabinet creates an executive team. London’s mayor appoints councillors8 to statutory portfolios for areas like housing, transport, and policing. This concentrates decision-making, makes responsibility visible, and ensures staff report through leaders who can be held accountable for results.

New York City (USA) — Diverse revenues create a capital structure. New York9 draws on property, sales, and income taxes, as well as tolls and congestion charges. This diverse mix allows the city to finance major projects, borrow against future income, and act without waiting on state or federal transfers.

What Must Be Done

Toronto needs modern governance tools to align elections with results. This requires three focused reforms: allowing municipal parties, creating a statutory mayor’s cabinet, and expanding fiscal powers. Each requires specific legislative or regulatory changes by the Province of Ontario.

Enable municipal political parties through changes to the Municipal Elections Act.

Every chief executive needs a board mandate. Toronto’s mayor has none, because councillors run as independents with no obligation to a city-wide agenda. Municipal parties would create that mandate by publishing platforms, tying councillors to collective outcomes, and letting voters judge council as a whole. This would connect local ballots to city-wide priorities and give the mayor the mandate needed to lead.

- Amend the Municipal Elections Act, 1996 to allow party names on ballots in Toronto, require platform publication, and create rules for registration, audits, and disclosure.

- Keep existing bans on corporate and union donations, and strengthen audit requirements for transparency.

- Use an Order in Council to set transitional rules so new parties can register and be ready for the 2026 municipal election.

Create a statutory mayor’s cabinet under the City of Toronto Act.

Large organizations rely on executives who own key files and answer for results. Toronto’s mayor has no such structure. Instead, authority is spread thin across committees and all of council, leaving no clear line of accountability. A statutory cabinet would change this by giving the mayor a defined executive team of councillors with portfolios like housing, transit, and finance — supported by staff reporting through them, and accountable through public mandate letters.

- Amend the City of Toronto Act, 2006 to create a formal “Executive Council” of councillors appointed by the mayor, each with a statutory portfolio.

- Require the City Manager, Chief Planner, and leaders of major divisions to report through cabinet members.

- Use an Order in Council to establish the first set of portfolios and require annual public reporting on performance.

Expand Toronto’s fiscal powers with amendments to provincial statutes.

Every leader needs diverse revenue streams and access to capital to deliver growth. Toronto’s tools are limited. Property taxes and user fees make up most of the budget, while major projects wait on unpredictable transfers from the Province or Ottawa. Strict borrowing limits also leave billions in development charges idle because projects must be fully funded up front. Other global cities raise money through a wide mix of tools, from sales taxes to congestion charges, and can borrow responsibly against future growth. Giving Toronto similar authority would allow the city to plan and fund its priorities independently, without waiting years for other governments. Importantly, these new tools should be paired with fewer conditional transfers, so the city is directly accountable to its residents for the taxes it raises and how it spends them.

- City of Toronto Act, 2006

- Amend Section 267 to allow Toronto to levy a local sales tax or receive a statutory share of the HST.

- Amend Section 255 to let the city issue revenue-backed debt tied to dedicated streams.

- Explicitly authorize tax-increment financing, letting Toronto borrow responsibly against future property tax growth from new development.

- Amend Section 267 to allow Toronto to levy a local sales tax or receive a statutory share of the HST.

- Highway Traffic Act: add a clause permitting Toronto to toll municipal expressways and create congestion charges.

- Assessment Act: amend Sec. 44 to require MPAC to publish land and building values separately, enabling split-rate property taxation.

- Use Orders in Council to designate eligible revenue sources and set transitional rules (e.g. CRA could collect HST shares on Toronto’s behalf).

- Recalibrate provincial transfers: reduce conditional grants tied to provincial priorities and replace them with predictable block transfers.

Common Questions

Will parties polarize local politics?

Experience in Montreal and Vancouver shows the opposite. Parties give voters clearer choices, tie councillors to shared platforms, and make accountability stronger. Ward representation would still exist, and strict rules on disclosure and donations would guard against partisanship.

Doesn’t a cabinet politicize the public service?

The mayor’s cabinet would be drawn from elected councillors with clear portfolios. Senior staff in those areas would report through them and the mayor, making priorities and performance visible. All directions would still flow through the City Manager to protect independence, while mandate letters and public reports ensure accountability stays with elected leaders.

Are new taxes inevitable?

No. New fiscal powers would give Toronto options, not obligations. Council could choose tools like sales taxes, road pricing, or split-rate property taxes to replace unstable transfers and reduce reliance on property taxes. Any new levy should come with clear communication about what it funds and what it replaces.

Is this constitutional?

Yes. Provinces have full control over municipalities. Ontario has already passed Toronto-specific laws and could do so again to allow municipal parties, a mayor’s cabinet, and new fiscal powers. These reforms are clearly within provincial authority.

Conclusion

Toronto is a global city, but it is run with outdated tools. Councillors are elected ward by ward with no citywide mandate. The mayor has no formal cabinet to carry out priorities. The city depends too heavily on property taxes, fees, and transfers from other governments. The result is a system where no one is clearly accountable, promises often stall, and Toronto cannot act at the scale it needs.

The fix is clear. Municipal parties would give voters platforms to choose from and hold council accountable for outcomes. A mayor’s cabinet would give the city an executive team with clear responsibility for housing, transit, and finance. New fiscal powers would allow Toronto to raise money fairly, plan long term, and rely less on unpredictable transfers.

The Province should pass these reforms by early 2026 so they are in place for the next election. Toronto can still lead—but only if we act. Every month of delay means higher costs, fewer homes, and more voters losing faith that the city works. Act now, and Toronto can stand again among the world’s great cities.