Keep Toronto Moving With Congestion Pricing

Summary

Toronto’s traffic gridlock is among the worst in North America, draining billions from the economy and robbing families of time every week. Expanding highways has failed — the 401 is one of the widest in the world and still jams daily. The proven solution is congestion pricing: charge a modest fee to enter the busiest parts of the city at peak times, reduce traffic substantially, and reinvest the revenue in better transit and roads. Cities like London, Stockholm, and New York show it works — traffic falls, commutes get faster, and the public comes to support it once the benefits are clear.

Goal: Reduce downtown commute times by 15–20% within two years (e.g., cutting a typical 45-minute peak trip by 7–9 minutes), while funding major transit improvements through pricing.

Background and Motivation

Toronto is grinding to a halt. Congestion here is now worse than almost anywhere else in North America, and the cost to the region is staggering. Studies estimate that traffic gridlock drains nearly $45 billion every year1 from the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area in lost productivity, wasted fuel, delivery delays, and family time that simply disappears. That number is not an abstraction: it shows up when shipments don’t arrive on time, when service vehicles can’t reach their customers, when employees show up late to meetings, and when families arrive home long after they should. Congestion is not just a nuisance—it is one of the biggest economic drags on the region.

The playbook Toronto has relied on for decades has been to add more lanes. Yet the evidence is written in asphalt across the city. Highway 4012 is one of the largest highways on earth, with more than 18 lanes at its widest point, and it remains a daily parking lot3. Every time the road has been widened, the relief has lasted months before traffic returned to previous levels. The province has even floated the idea of tunnelling under the 401 to add still more lanes—a multibillion-dollar project that would deliver the same failed result. Economists call this induced demand: when you increase supply of a scarce good without managing demand, it simply fills back up. No city has ever built its way out of congestion, and Toronto will not be the first.

We have seen the price signal work the other way. When tolls were removed from Highways 412 and 418 east of Toronto, traffic volumes surged almost overnight and those once-clear routes clogged. The same happened when tolls were lifted4 on Highway 407 East. Make driving cheaper, and more people drive until the road jams. This is the mirror image of the 401 story: in both directions, the pattern is the same. If driving is priced at zero, congestion is the result.

That is why congestion pricing is different. Instead of trying to pour billions more into concrete, it uses price to manage demand on the most valuable roads at the most valuable times. By charging a modest fee to enter the busiest parts of downtown at peak hours, cities have been able to cut traffic volumes5 by over 15% and raise average travel speeds. London’s system removed tens of thousands of cars a day from the core, and journey times improved immediately. Stockholm’s cordon6 reduced cars entering the city by more than a fifth, making trips more predictable and reliable for those who remained. Singapore’s system adjusts charges7 in real time to hold speeds steady, ensuring goods and services can move through the city without constant delays. In New York, the first North American congestion zone has already taken 43,000 cars a day8 off Manhattan’s streets.

The payoff is shorter commutes, faster deliveries, and less wasted time across the economy. Congestion pricing means a plumber or electrician can reach two customers in a morning instead of one. It means trucks delivering goods don’t sit idling for an hour on clogged arterials. It means a parent gets home for dinner on time. These are the metrics that matter: shorter, more reliable commutes; goods delivered when promised; services arriving on schedule; billions saved in wasted time and lost productivity.

Toronto has reached the point where doing nothing costs more than doing something bold. Every year congestion worsens, commute times lengthen, and the economic drag grows. The province’s idea of tunnelling under the 401 is the latest example of a strategy that spends huge sums for no gain. Without congestion pricing, families, businesses, and the economy will keep paying the price. With it, Toronto can finally put value on what matters most: people’s time, the movement of goods and services, and the competitiveness of the entire region.

Real World Examples

London – Faster journeys and reinvestment.

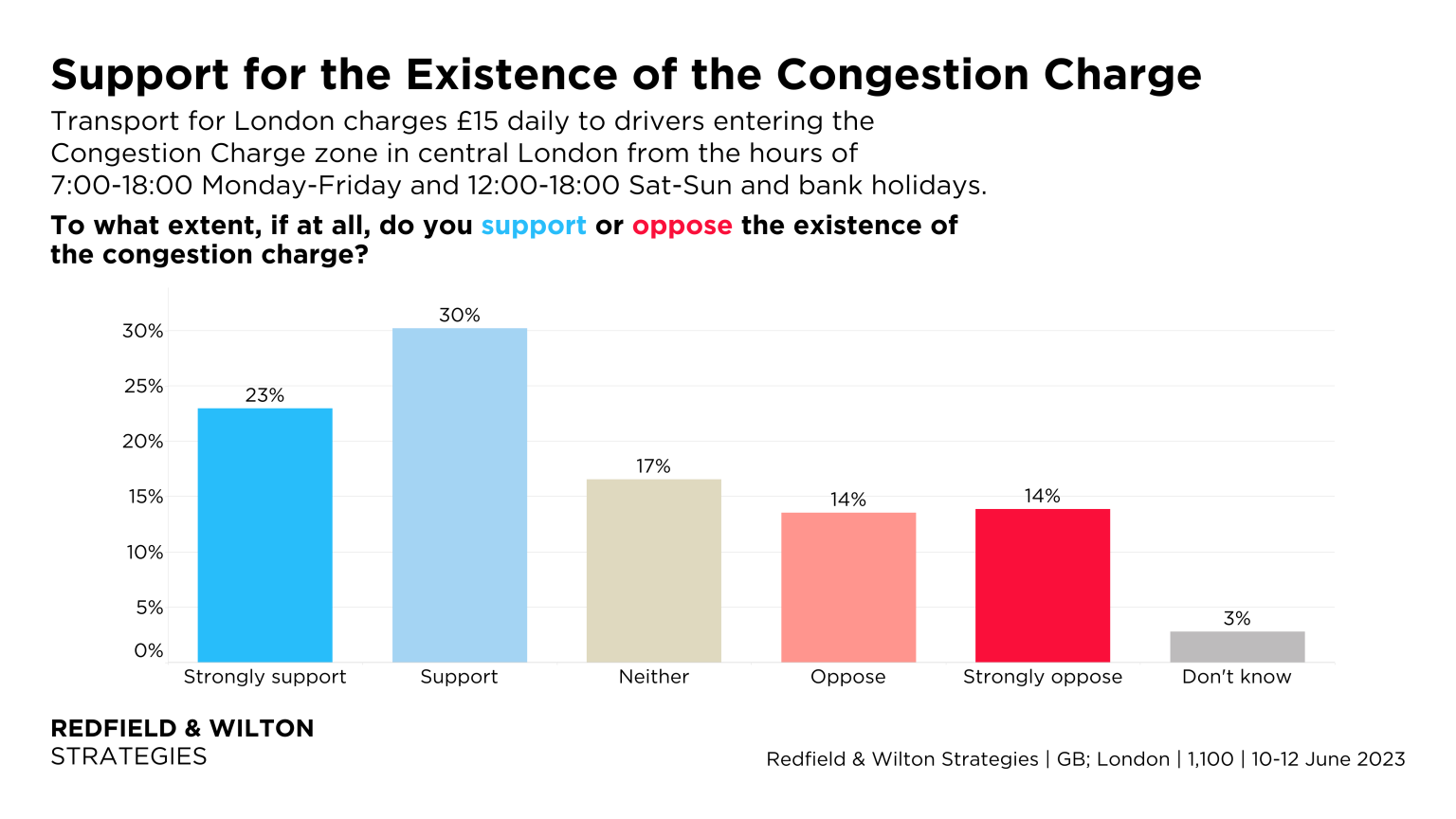

London launched congestion pricing9 in 2003. Within a year, traffic entering the central zone fell by nearly 20% and average travel speeds rose by 14%. Tens of thousands fewer cars entered the core each day, saving commuters minutes on every trip. Importantly, the £300 million raised annually was reinvested in public transport, making buses and trains more reliable for millions of riders. Despite skepticism and disapproval prior to launch, the move is now widely supported by Londoners.

Stockholm – Reliability across the network.

Stockholm tested congestion pricing as a pilot in 2006 and made it permanent once results were clear. Traffic volumes into the city dropped by over10 20%, and travel times on key arterials became measurably more predictable. Businesses saw delivery times improve, and commuters reported greater consistency in how long their trips took. Initial opposition turned into majority support once the benefits were felt directly.

Singapore – Managing speeds, not ideology.

Singapore has operated electronic road pricing since the 1990s, with charges adjusted in real time to keep traffic flowing11. Prices rise and fall depending on conditions to hold speeds at 45–65 km/h on expressways and 20–30 km/h on arterial roads. This system ensures that goods, services, and commuters can plan with confidence that the network will perform at a predictable level — a direct productivity gain for the city-state’s economy.

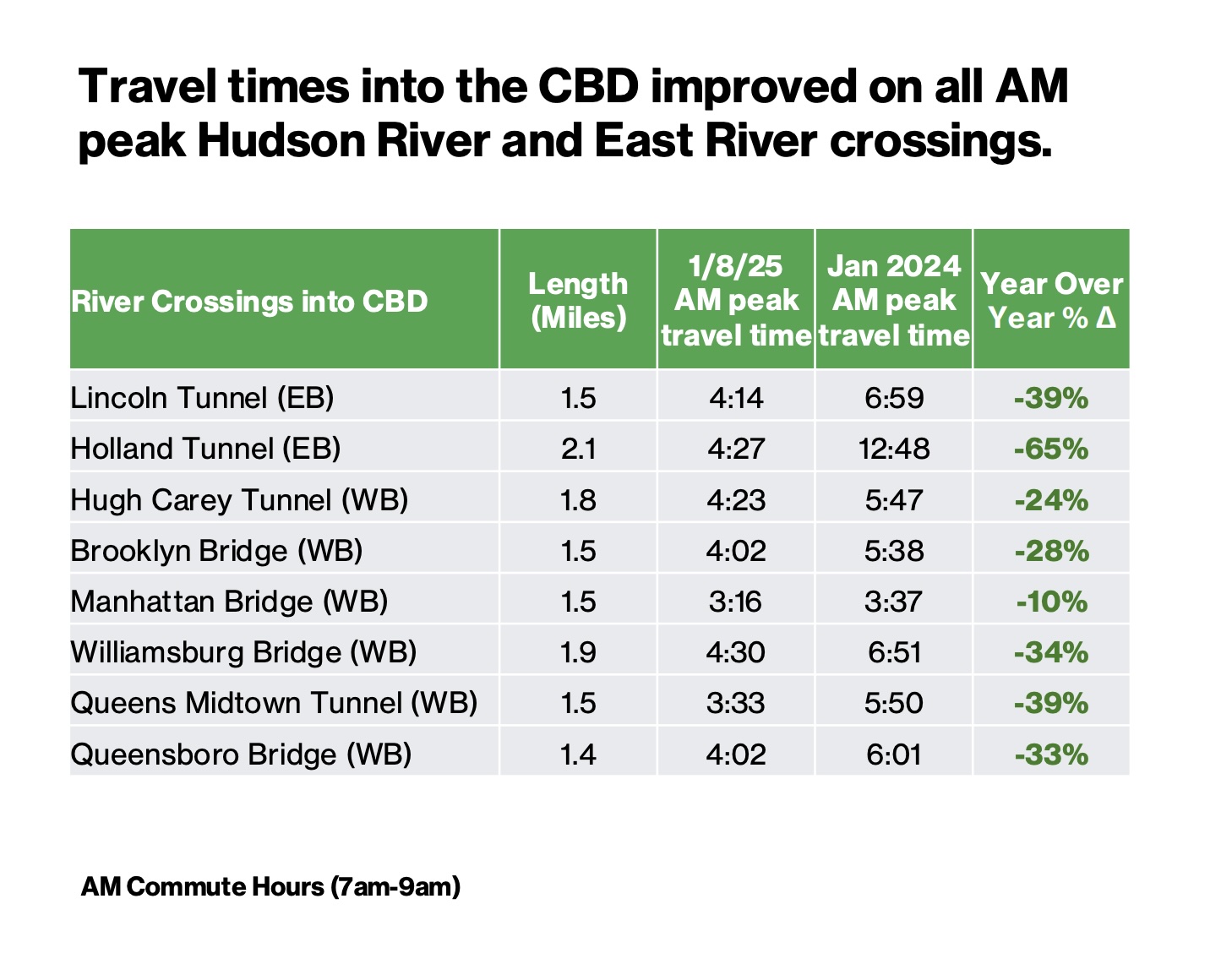

New York – North American proof.

In 2024, New York introduced a congestion charge south of 60th Street in Manhattan, the first large-scale program in North America. Early results showed about 50,000 fewer cars per day entering the zone and cut traffic by over 25%12. The program unlocked over $1 billion annually for transit upgrades, while travel through Midtown became faster and more reliable.

What Needs To Be Done

Create a downtown congestion pricing zone. Toronto should introduce a pilot zone covering the core south of Bloor, between Bathurst and Parliament. Pricing entry during peak hours at $10–15 per day can reduce traffic volumes by 15–20%, cutting journey times and making deliveries more reliable. Net revenues should be locked into transit, road upkeep, and active transportation improvements, with annual reporting to build public trust.

- City Council to pass a by-law under the City of Toronto Act designating a Congestion Pricing Pilot Area.

- Province to amend the Highway Traffic Act to authorize municipal congestion charges and camera enforcement.

- Establish a Congestion Pricing Revenue Fund requiring all net revenues to be reinvested in transportation.

Introduce dynamic highway pricing across the GTA. On 400-series highways and expressways in Halton, Peel, York, Durham, and Toronto, Ontario should adopt Singapore’s model of adjusting tolls in real time to maintain average speeds of around 60 km/h. This ensures reliability for goods movement and commuters alike, avoiding billions in lost productivity from traffic jams on the 401, DVP, Gardiner, and other key routes.

- Province to amend the Highway Traffic Act and Toll Highways Act to permit variable electronic road pricing.

- Install electronic gantries on pilot corridors (e.g., Gardiner, DVP, Highway 401) with dynamic rates tied to maintaining 60 km/h average speeds.

- Mandate quarterly performance reporting on speeds, traffic volumes, and revenues in each region.

Guarantee fairness and predictable exemptions. Congestion pricing must be designed to improve equity, not worsen it. Exemptions for emergency vehicles and wheelchair-accessible vehicles should be standard. Targeted discounts for low-income drivers and residents living inside the zone can follow London’s model, ensuring benefits are shared fairly across the city and region.

- Province to amend the Highway Traffic Act to enable targeted exemptions and discounts.

- City Council to establish an application process for residents and low-income drivers within the zone.

- Direct City staff to publish annual equity audits of who pays and who benefits.

Invest in alternatives before launch. Congestion pricing only works if people have other ways to move. Revenues should expand GO frequency, improve TTC reliability, and build park-and-ride facilities at transit hubs. Launching pricing alongside visible service upgrades will build public support and demonstrate the payoff.

- City Council to allocate initial revenues toward TTC service expansion and active transportation infrastructure.

- Province to dedicate a share of funds to GO Expansion, targeting 15-minute service on Lakeshore and Kitchener corridors.

- Require a joint City–Province public report before launch, outlining transit and infrastructure upgrades tied to the program.

Common Questions

Won’t this hurt businesses downtown?

No. London and New York showed downtown business activity stayed strong. Easier commutes mean more customers, not fewer.

Isn’t this just another tax?

No. It’s a user fee on the most congested roads, with every dollar transparently reinvested in transit.

Won’t drivers just go around the zone?

Stockholm and London found the opposite — traffic outside zones stayed stable or even fell. Most people switch modes, not routes.

Is this unfair to low-income drivers?

Most low-income households don’t drive downtown. Exemptions and transit credits ensure fairness. Wealthier commuters who use the roads most often will pay the most.

Why not just add more lanes?

History shows it doesn’t work. Highway 401 is one of the widest in the world and still congested. Adding lanes only adds more traffic. Pricing is the only proven fix.

Toronto isn’t an island – there are many ins and outs of the city. How will we enforce it?

London isn’t an island either — it runs a cordon with ~250 ANPR cameras on boundary/city-centre streets. New York (also not an island in practice for traffic) runs ~110 detection points with ~1,400 scanners covering hundreds of approach lanes. Toronto can deploy a similar network

Conclusion

Toronto has reached the point where congestion is no longer just an annoyance but one of the greatest drags on the region’s economy. Billions of dollars and countless hours are lost every year as highways clog and downtown streets grind to a halt. Building more lanes has failed for decades, but congestion pricing offers a proven path forward. A downtown zone can free up space in the core, while dynamic pricing on GTA highways can keep traffic moving at reliable speeds. Together, these policies will unlock shorter commutes, faster deliveries, and billions in productivity gains. With clear exemptions, targeted discounts, and guaranteed reinvestment in transit and roads, congestion pricing can deliver a system that is faster, fairer, and more reliable for everyone.